WALKING DEBT

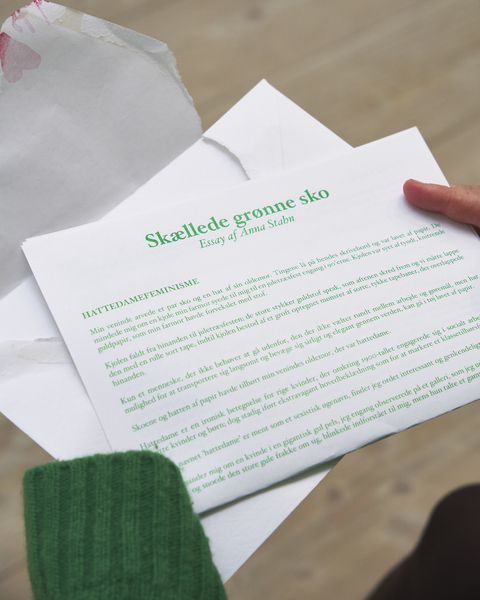

My friend inherited a pair of shoes and a hat from her great grandmother. These things lay at her desk and were made of paper. The shoes and the paper hat had belonged to my friend’s great grandmother who was a hat lady.

They reminded me of a dress my grandmother sewed for me for a Christmas party sometime in the 90s. The dress was sewn from thin, crackling gold paper that my grandmother had mistaken for fabric.

The dress fell apart at the Christmas party; the large pieces of gold fabric burst and we had to piece it together with a roll of black tape until the dress consisted of a roughly sketched pattern of black thick lengths of tape overlapping each other.

Only a person who doesn’t need to go outside, those who doesn’t topple around between work and chores but have the option of transporting themselves slowly and move through the world neatly and with elegance can wear clothes made of paper.

Hat lady is an ironic term for rich women who engaged in social work with marginalized women and children around the beginning of the 20th century; still wearing extravagant headgear, however, as to mark a class affiliation.

Even though the name ’hat lady’ is meant as a sexist nickname, I find the word interesting and identifiable.

The word reminds me of a woman in a tremendous yellow fur coat I once observed at a gallery where I exhibited. She tossed and twined the big, yellow coat around her, winked at me knowingly while speaking in an old-fashioned, affected manner.

The word reminds me of everyday mornings walking nonchalantly through the city in a complicated attire; a turtle in a leash and coffee to-go while I observe people storming to work or already working.

It reminds of the economic upper class weaved together with the creative one – artworks being acquired by people who have profited or been born into wealth, skimmed the cream and now they have tossed their love, time and money at art, wishing to exchange capital for authenticity, pay for my butter, my hat, my rent.

This reminds me of the class barriers, existing so undisturbed in the art world. They can seem invisible except when it comes to last names, expensive objects, self-confidence and contacts.

My work as an artist have affected me in a direction where everything is measured and results in objetcs. In dresses, shoes, bills, cups of coffee, pallets of clay and glazing, paper goods and plane tickets.

Maybe that’s the reason for this text so quickly starts being about leaves of lettuce, about walking green papers.

I’m calling the art market a ’cowboy land’; when you think about it, art is one of the only unregulated markets left that is still legal. Where equal pay, unions, working rights, logic pricings don’t exist. A market where money laundering, flipping, underpayment, free work and unequal pay flourish in a barren garden for the few.

Kunstforeningen GL Strand lies in a row of chubby brick houses painted in dusty colors by the old fish market in central Copenhagen.

Once, the rancid smell of fish were paramount in Copenhagen, fish from the ocean around the docks were exported from here and so the smell of fish was a smell of money.

The smell of slimy, scaled money commingled with a smell of shit because of the toxic, poorly constructed buildings with their asbestos and foul sewerage. Shit from upper and lower class alike were mixed together.

The women living at the rearest end of the houses’ backyards or outside of central Copenhagen but walking the long way to the Gammel Strand fishmarket everyday were called fishwives. My fantasy of the fishwives; they stood there, yelling, selling fish at the square of Gammel Strand right next to the houses and societies of the hat ladies.

I imagine tthe fishwives as small chubby women with hoarse voices, bloody, chequered scarves and coarse hands.

I imagine them in this area of Gammel Strand, serving fish in newspapers which is later picked up by Wolt deliverers on bikes and scooters. The fishwives handed out paper hats and shoes filled with greasy fresh fish to the ladies with paper hats.

Even though the word ’fishwife’ is meant as a sexist nickname I find the word interesting and identifiable.

It reminds me of the way I speak loudly, walk heavily, get into trouble by teasingly unveiling an opinion.

It reminds of the times I have slogged, had three jobs, didn’t sleep, ran for the bus to get back to work, got filth and dirt on my clothes. Baked ceramics while on my period with chinked pants for the pleasure of a group of people my own age just so I could pay my taxes the week after. Smelled of fish and ceramics and period blood.

Inside of me are two women; one is a fisherman’s wife, the other is a hat lady feminist. In this constellation as an artist, am I then a fishwife or a hat lady? Do I wrinkle my nose self-righteously or do I sell fish? Ladies and gentlemen: both.

- Excerpt from Anna Stahn’s work ”Loveletter” a written for walking debt Gl. Strand 2022

The exhibition idea for Walking debt has emerged from Anna Stahn’s own ambivalent experiences with life, cosumerism, culture economies and possibilities in the city. For the shaping of her works, Anna Stahn has drawn inspiration from various tales of female life historically linked to the area around GL STRAND in Copenhagen; hat ladies of the Copenhagen bourgeoisie, living in the row of houses on Gammel Strand, maybe buying fish from these fishwives; and references to the sex workers luring as sirens in the neighborhood alleys named Laksegade (Salmon Street) and Hummergade (Lobster Street).

With the exhibition title Walking Debt, Anna Stahn presents the urban space as a scene, on which we all stroll exchanging all sorts of capital – economic, social as well as cultural capital. In general, contrasts are a recurring focus for Anna Stahn, who is preoccupied with how life is simultaneously filled with beauty and ugliness, fragility and power. And, as in this exhibition, with how we navigate through visible and invisible structures and hierarchies – perhaps being a boastful fishwife in one moment and a noble hat lady in the next.

- Pernille Fonnesbech, curator Gl. Strand